The Landscape of Grief

People have been dying for a long time, so you would think that we’d have grief figured out by now. You’d expect that everyone would know what to do to comfort a friend who has lost a loved one, but we seem to have forgotten. You’d anticipate that society would have a great tome of accumulated wisdom we could page through for guidance, but apparently it’s been misplaced. Grief has become the individual’s problem.

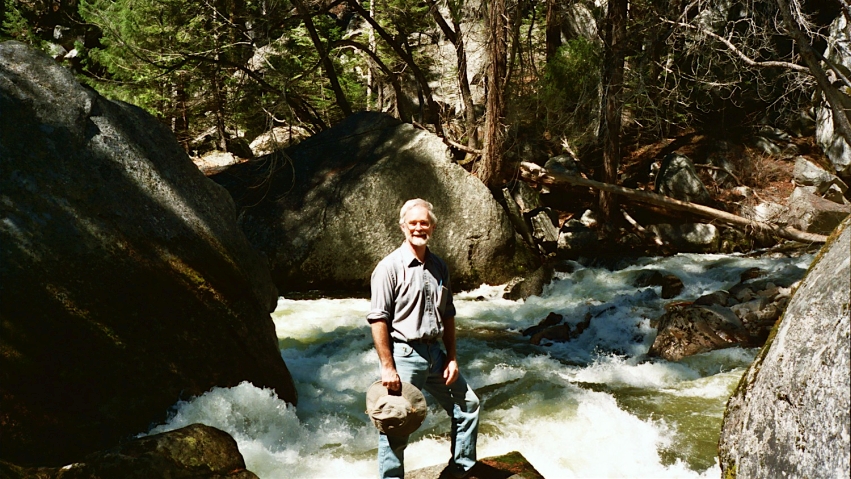

I ran into this wall of unknowing when my wife Evelyn died some years ago. We were in our 40s and her unexpected death left me devastated. Because my friends were young and hadn’t lost anyone close, they didn’t know how to help, and the books I read were useless. Thankfully, I found acceptance and understanding in an online support group. I also went hiking in Yosemite, and the wonder and light of the mountains guided me through grief’s darkness.

Life’s Fragility

If we love anyone, we will grieve them when they die—and it will be harder, and last longer, than we ever expected. It would be helpful if we were familiar with the basic landscape of grief ahead of time.

I blame modern medicine. A century ago, after World War I and the flu pandemic of 1918 left millions of people lying dead in the streets of major cities around the world, everyone knew how fragile life was. When penicillin and vaccines were developed, and faulty hearts and worn-out joints began to be replaced, it seemed that living to 100 might become the new norm. We stopped talking about death as an everyday reality, and talked instead about the next experimental drug. Now, when someone dies, even if they are in their 90s, we blame it on a medical mistake.

Many of us don’t like to talk about death. We want to ignore grief, hoping it will go away on its own. If someone says they’ve been planning ahead and are writing their obituary, setting up their will or deciding what they want for their funeral, many of us find it creepy and think it will entice Death to stop by.

It’s almost impossible for those who have never lost anyone close to comprehend the impact, anguish and exhaustion of grieving. It feels like a fire has burned down our home, blackened our bones and left us standing in smoldering ruins. No one understands grief until Death comes and lights the match.

When Ev died, I expected the bulk of my grief to be over in a month. I wasn’t close. Even with the help of my faith community, it was a year before I could begin putting the pieces of my life back together with any sense of hope. I began writing to understand my grief and to find a path through its wilderness. Now I write to share what I have learned with others.

An Offer of Help

Many people are uneasy dealing with someone’s grief, partially because of all the emotions and tears, but also because they feel helpless and sense they won’t be able to take the pain away. Yet every day, people around us lose parents, spouses, friends, children and babies because of illnesses and accidents, so there is a great need for our response. Now people we know are dying because of COVID-19. If you don’t know what to say to someone who is grieving, simply let them know that you’d like to help in some way.

Whatever you do, do it with kindness that goes beyond the polite. If you’re willing to listen, ask how they are doing. Talk to them about their loved ones. Even if you have suffered the same kind of loss, don’t say that you understand. You don’t know where a friend is hurting until you listen to them. Offer to bring over dinner or bake a pie. Offer to go grocery shopping for them. Because it’s risky right now to get together and talk over coffee, you can call or send notes to let them know you’re thinking about them. Do something to help them bear the weight of grief. PM

Mark Liebenow of Peoria is an award-winning author, essayist and poet whose work has been published in four books and more than 40 journals. To learn more, visit markliebenow.com or find his blog at widowersgrief.blogspot.com.