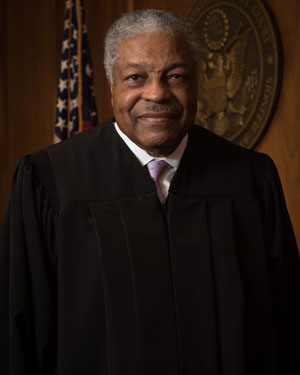

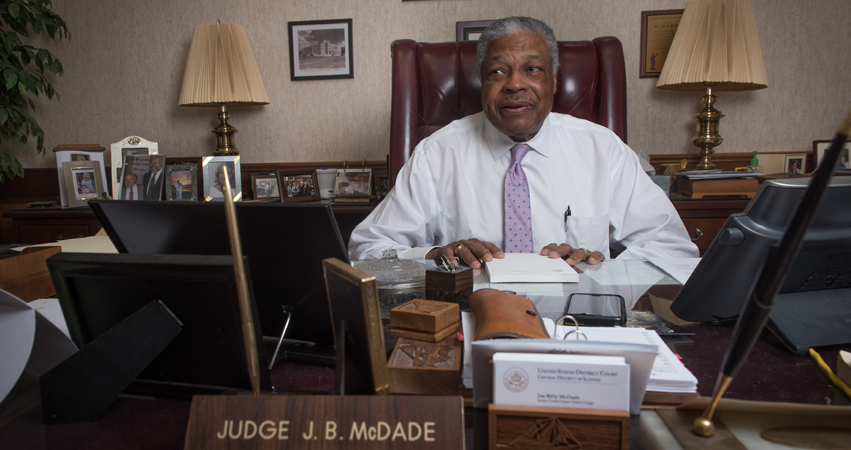

Hon. Joe Billy McDade

Born in Raccoon Bend, Texas in 1937, the Honorable Joe Billy McDade is a senior district judge of the United States District Court for the Central District of Illinois. Appointed in 1991, he also served as chief justice of the court from 1998 to 2004. He holds a bachelor’s degree in economics and a master’s degree in psychology from Bradley University and a juris doctor degree from the University of Michigan Law School.

In addition to nearly four decades of judiciary experience, Judge McDade’s life has been marked by an enduring commitment to civil rights and education. As a student at Bradley University, he was a star player on the legendary basketball team that claimed the school’s first NIT championship title in 1957. He received the Watonga Award two years later—the highest student-athlete award given by the university—and the Distinguished Alumnus Award in 1990. A member of the Bradley Athletics Hall of Fame and Greater Peoria Sports Hall of Fame, he has received a string of awards from churches, clubs, nonprofits and other organizations for his community service and leadership.

Judge McDade spent much of his childhood as an orphan—his mother passed away when he was just a year old and his father died when he was 10. In their place, his grandmother Judy Sherrill raised him and his sister Wilma. Due to school segregation policies, he had to attend school in Houston, Texas—at 60 miles away, it was the closest school to his home that accepted African-American students. Persevering against all odds, he completed multiple degrees and worked his way up to one of the most prominent positions in the judiciary, never forgetting his humble Texas roots.

McDade has four children with his first wife, Mary McDade, a civil rights activist and appellate judge in Illinois’ Third District. He is now married to his wife, Carolyn, and assumed senior status in his federal judicial service in 2010.

Your early years were marked by poverty, working in the cottonfields with your grandmother. Tell us about that.

If you were black in those days, you worked as a domestic for a white family, or you worked in the country in the cottonfields—that’s what my grandmother did. I would go into the fields with her when I was three or four. Even when I was five years old… I was trying my best to help her pick cotton.

Did you always have a passion for education?

Yes. Raccoon Bend had a one-room schoolhouse, and one of the teachers lived two homes away. She always asked my grandmother if I could go to school with her, and one day my grandmother allowed me to go. I was too young to participate—I must have been three or four. They had a calendar on the wall of a pig dressed like a person, and I spent my time that day drawing this pig. The teacher told my grandmother what a great student I was, and how impressed she was with my drawing. Maybe that initial excitement from doing something educational set the tone.

My grandmother was literate—she could write and she could read—but she had no [formal] schooling as far as I know. She must have had a great respect for learning, because my dad spent at least one or two years at Prairie View A&M University, a traditionally black college. She always made sure that I went to school, and she always took great pride in my success.

When I was in school in Houston, the whole culture of the black community in the 1950s was [about] education. It didn’t matter if you were at the bottom of the economic rung, like my grandmother, whether or not you were a black businessman or a teacher—all of the parents wanted them to do well in school. They truly believed that education was a way of progress for blacks in this country.

When did you first form an interest in becoming a lawyer?

The only time it came up was an incident that I’ve often repeated: A broom salesman—a street peddler—came by our house, and my grandmother was talking to him about buying a broom. I could see that she was weak then… she was going to buy a broom, but we needed the money for rent. I remember my frustration. It caused me to spontaneously say, “Mama J, we can’t afford a broom! When I grow up, I’m going to be a lawyer so I don’t have to buy a broom from anybody.”

I don’t know where that came from… I’ve thought about it for 50 years. I knew no lawyers. For some reason, I felt the law was a protector that would allow me to be free.

But once I said that, my grandmother and neighbors picked up on it. We would travel from Houston to Raccoon Bend by bus, and I would say things like, “Mama J, how far are we from Raccoon Bend?” And she would say, “Five miles.” And I said, “No, it’s three miles.” She said, “Boy, we just passed a sign that said five miles!” I said, “I don’t care about that sign. We’re only about three miles away from Raccoon Bend.” She started telling everybody: “He is going to be a lawyer because he even argues with a signpost!”

What led you to Bradley University?

I graduated [high school] in 1955. And in 1953, a white millionaire, E.E. Worthing, died. He had earned his wealth by renting homes and loaning money to blacks in Houston’s Fourth Ward. When he died, he created a “scandal” by leaving all his money in trusts to provide scholarships at the three black high schools in Houston. Each of the high schools received four $1,000 scholarships yearly. I was one of four students at Jack Yates High School who got an E.E. Worthing scholarship

My first thought was to leave Texas and apply to school up north, because out of ignorance we all thought the north was a location of freedom for blacks. I had a civics teacher, Mr. Green, who [said] there was a small liberal arts school in Peoria, Illinois, which was affiliated with the University of Chicago. Well, that was false information, but I didn’t know that. So on his recommendation, I applied to Bradley. It was the first school to accept me.

How did you meet some of your teammates on the basketball team, like Shellie McMillon and Curley Johnson?

When I got to Peoria, I was standing around… figuring out how I was going to get to campus from the railroad station. Shellie McMillon came up, introduced himself and asked if I was going to Bradley… He had never heard of me, and I had never heard of him, which he took as something strange because they [Shellie McMillon and Curley Johnson] were the talk of the state. They expected, rightfully so, that everyone who came to Bradley playing basketball would know of them. And here I am and I didn’t. So they figured, “Ah, this guy must be so great, because if he doesn’t know us or recognize us… he must be really good!”

Several of us went out that night and I had my first beer. We didn’t go to the College Inn, which was the Bradley hangout at the end of Main and Western, because they didn’t serve blacks. We had to go to downtown to the American Legion on State Street. After I told my story, they asked if I was any good at basketball. I told them I was the fourth-best player on my high school team.

So they said, “Well, we go up to the gym and play every day at 3pm—we want you to go with us and play.” On their advice I went out for the freshman team. I made it, and in fact, I was a starter. I ended up getting a partial athletic scholarship.

Along with McMillon and Johnson, you were among the first African Americans to play at Bradley. What kind of discrimination did you experience on the road in the late 1950s?

We had to play in St. Louis, Tulsa, Houston… and they were all discriminatory places. We could not live together in the same hotels in the same place. We had to have a police escort out of Tulsa. My grandmother saw us play in Houston, and she heard them use the N-word and spit on us. We got assaulted by the white players. As more and more black players played for the other teams, that lessened and things became better. But we were at the vanguard, where it was rough.

You received your J.D. in 1963 from the University of Michigan at the height of the civil rights movement. What was it like to find a job at that time?

I went through the placement process at the Michigan Law School. The interviewers were impressed, but they always said, “Our firm isn’t ready to have a black lawyer. We don’t think our clients would put up with that.”

I came back to Peoria and interviewed at all the firms here that had several lawyers—and they told me the same thing, but they would first take me to lunch at the Country Club. I think they thought that made me feel better, but it did not.

After those job rejections, you were a staff attorney for the Antitrust Division of the U.S. Department of Justice in Chicago for two years. What brought you back to Peoria?

I was recruited to come back to Peoria to work at First Federal Savings and Loan Association. A.D. Theobald was the chief executive at First Federal, and he was a very bright and civic-minded man. He and other Peoria leaders didn’t want to have affirmative action forced on them—they wanted to be out front with it.

We were looking for housing in Peoria. Knowing that I was a former star basketball player at Bradley, my wife expected that it would be a very easy objective. But to my embarrassment, people would say, “Joe Billy, we loved you as a basketball player, you were so great, my kids admire you so…! But we can’t rent to you.”

I called Mr. Theobald and said we couldn’t find a house. The Association had some houses in stock that they had foreclosed on, so we rented from First Federal. And that lasted only about 10 months.

Then Max Lipkin, Corporation Counsel for the City of Peoria, called me up one day and said, “I’m the head of the Legal Aid Society. How would you like to come on as the executive director? It’s just a one-man office.” It was a salary cut, but I’d be practicing law. One year later, I got a federal grant to increase the number of attorneys to five, so I hired four other attorneys. I’m very proud of that because that really was the birth of the legal services program here. Now you have the outgrowth of the program I started, which is Prairie State Legal Services.

What was your role with the Peoria NAACP during this time?

Mary and I became very active in civic affairs, and obviously the NAACP at that time had become a force. We became closely connected with [NAACP president] John Gwynn and the NAACP. John had been marching to get CILCO [the former Central Illinois Light Company] to hire blacks. I had known a vice president at CILCO during my Bradley years—the family had sort of become surrogate parents and we were very close. I knew that he had started out as a meter reader; he didn’t go to college. And I knew a lot of other CILCO officials did not have degrees when they started at the company. So, that was the premise of my argument against their requirement that “blacks must have high school diplomas.” That was not fair because they didn’t have them—and I named names! It was a very effective presentation.

Why did you decide to leave the Legal Aid Society?

After about three years, I got burned out because I had just over a thousand cases a year. I started seeing people as numbers, rather than individuals with a lot of problems that need help. They deserved better. We needed somebody who was fresh—who was willing to do what I was willing to do the first two years. I resigned from the agency and went into private practice.

You were an associate circuit judge from 1982 to 1988, then ran for circuit judge in the Tenth Judicial Circuit as a Republican. What was that campaign like?

I was supported by both Democrats and Republicans. A lot of Democrats thought I was a Democrat, and Republicans thought I was a Republican. I think both groups thought that I was a good person.

Francis Boyle was instrumental in helping me become what I am. He was a farmer who lived by Hennepin, Illinois, one of the most decent people I’ve ever met in my life. He was an ardent Democrat—and he worked awfully hard for me in Marshall County. Besides his support for me politically, he was just a fine man that represented the best of what we could be.

I’m very proud of that. That no matter what the label is, I’m someone you can trust to do the right thing, to work hard and be the best that I could be.

In 1991, you were nominated by President George H. W. Bush to a temporary position on the U.S. District Court for the Central District of Illinois—a position that was later made permanent. What memories do you have of that process?

Usually on the district court judge level, the senior senator of the party in office makes a recommendation to the president. But in 1991 I was a Republican, and there were no Republican senators. The two senators from Illinois were Senator [Alan] Dixon and Senator [Paul] Simon—both Democrats. The leading Republican was Congressman Bob Michel, so he was the one who made a recommendation to the president—I was one of four that he recommended. He had followed my career, and he knew about me.

We all had to go to Washington, DC to be interviewed by the Justice Department. Unbeknownst to us, Congressman Michel had indicated who his personal choice was. Fortunately for me in this case, the Justice Department agreed with Congressman Michel’s choice that I was the best person.

My good friend Mike McCuskey, who was a Democrat and federal judge—he’s now back on the state bench—put in a word about me with Senator Simon. When I went to Washington to be interviewed, at his suggestion, I stopped by and paid respects to Senator Simon. That was the best thing I could’ve done because Senator Simon arranged to have a subcommittee of the Judiciary Committee appointed under his leadership just to take up my nomination.

What has been the greatest challenge you’ve experienced over the years?

What has been the greatest challenge you’ve experienced over the years?

When I was a practicing lawyer, I had a case in small claims court, and I thought I had the facts and the law on my side. My opponent was a very prominent lawyer in town. I lost the case, and as I was leaving the courthouse, my despair and disappointment were obvious. And this lawyer came up to me, put his arm around my shoulder and said, “McDade, when you’ve been practicing law as long as I have, you’re gonna win some that you shouldn’t win, too.” He was trying to console me, but I said to myself, “That’s not the way the system should work.” If you’ve got the law and the facts on your side, you should win no matter who your lawyer is. So, that’s been the way that I operate.

You’ve helped out a lot of people along the way. Has that been your biggest reward?

Yes, and that’s particularly true in criminal matters because people don’t realize that a lot of people—particularly in the black community—with all the disruptions in their families and things like that, they haven’t had the advice of fathers or other adults in their life. So they have taken wrong paths. But when they find someone who treats them with respect, acknowledging their faults, acknowledging the lack of discipline in their life—it takes time to explain why there has to be consequences for one’s actions and treat them as you would treat your own children who have done wrong. They respond to that. I’m affecting lives because I care. You don’t excuse them, but you treat them with dignity and respect.

What have you learned as you look across the bench into the eyes of those you are sentencing? What frustrates or encourages you?

They’ve got more smarts than I had when I was that age. They have more courage—even though that courage is manifested in a bad way, it still takes courage. I despair because I see wasted lives. Some of these kids could’ve been saved if they had somebody in their life. I tell them that I take the time to talk to them because I believe in redemption.

I tell my story and how I got a second chance. I tell them how every Saturday we would go play basketball in the court outside the school. Houston is hot and humid, so the kids would take a break—and they would break into the cafeteria and get a soda pop or an ice cream bar, and then come back and play. I never went because I was a good kid. But one day, for some reason, I went with them and I got an ice cream bar or something. That Monday in homeroom, over the speaker came, “Would the following boys report to the principal’s office…”

At this time I was up for a scholarship, and I was waiting for my name to be called. And I said to myself, “Oh my god, my grandmother is going to be so hurt. I’m going to embarrass her! My whole life has been wasted by this!” My name was never called.

I went on to get my scholarship, and I am where I am now. About 10 years after I graduated from high school, I went back to Houston and ran into one of those fellas. I asked, “Do you remember when we broke into the cafeteria and were called to the principal’s office? My name was never called… why?” He said, “Joe Billy, we knew you were a good kid. We didn’t want to ruin your life.” So I tell these guys that someone gave me a second chance.

What would you like your legacy to be?

I have tried to live a principled life. I never want anything or anybody so much that I would violate my principles. So if that means I have to cut grass or pick cotton, I can do that. I would like them to say he was a principled person who tried to live by good standards. I would like people to say that I tried to do the right thing, and I was respectful of people. PM