“Dynamite Crowe” and Darrow’s Nemesis

Robert Emmitt Crowe was born in Peoria on January 22, 1879, the last of eight children to Patrick and Annie Crowe, Irish immigrants who came to America in the mid-1800s. The large Crowe clan lived in the 500 block of Perry Avenue, but Robert would only know Peoria for a short time. Before he was of school age, his father, a gas lamp lighter for the city, moved the family to Chicago, where Robert would begin a career in law. Soon he would become the city’s top prosecutor, known today for a classic showdown with famed Chicago defense attorney Clarence Darrow.

There are no books written specifically about Robert Crowe, but there are plenty about Darrow. The authors of these books do not diminish Crowe’s role as Darrow’s antagonist, nor his short upbringing in Peoria—which, as it turns out, was a tumultuous one for the Crowe family.

The Investigative Imagination

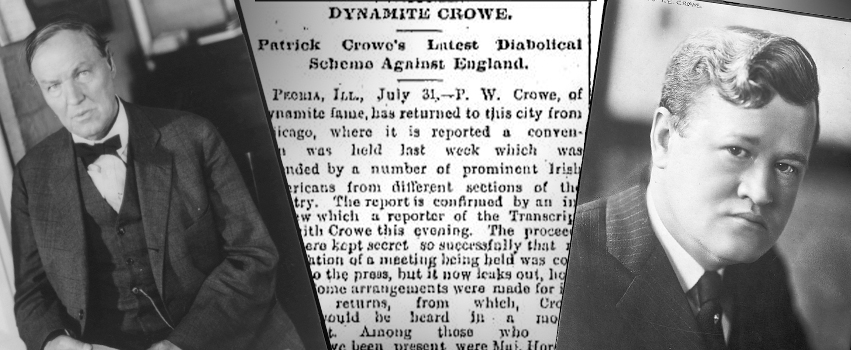

During the Irish potato famine of the 1840s, Patrick Crowe emigrated to the U.S., as did many others from the County Galway region. Crowe carried a grudge against the British government and soon joined a group of Irish nationalists known as the Fenian Brotherhood, whose goal was to free Ireland from British rule.

Bombs went off in London and other key British cities. Then on May 6, 1882, a British royal named Lord Frederick Cavendish and his under-secretary were ambushed and gunned down in a Dublin park. The assassination was tied to radical Irish groups both in Europe and abroad. Soon, the investigation reached America.

Fenian chapters were active in cities like Peoria, where Crowe was a member. Shortly after the British bombings, a zealous group of reporters saw Crowe carrying a tin can on his rounds lighting the lamps. “Suppose that can in his hand was really a bomb to be thrown at the King of England?” they speculated. They became convinced (possibly influenced by alcohol, as one report goes) that Crowe was behind the bombings—and possibly the assassination, too. As the Peoriana notebook put it years later: “The imagination of the news hounds began working.”

A wire story was sent out, and Crowe became international news. “Dynamite Crowe” became his moniker in the headlines. Even detectives from Scotland Yard arrived in Peoria to follow his every move.

Crowe never shied away from his hatred of British policies and even fueled speculation by bragging about Fenian-financed, dynamite-making factories in Peoria and New York. In the end, his reported arrest in Peoria by the U.S. Marshall was fabricated, and the “hoax,” as it would be called, dropped out of the news. But it’s the reason Patrick Crowe left Peoria.

A Crime in Chicago

To the Clan na Gael—the Irish activist group which replaced the Fenian Brotherhood—Crowe was a hero, and they invited him to Chicago. The family moved from Peoria to Chicago’s 19th Ward, a poor neighborhood made up of mostly Irish immigrants.

Robert was only three at the time. He attended Chicago public schools, graduated high school and studied law at Yale University. In 1903, he returned to Chicago and opened a private practice, and his political aspirations eventually led to an appointment on the bench as a criminal court judge.

Described as “jut jawed and thin-lipped, with a steady gaze and intimidating manner,” Crowe was elected Cook County state’s attorney in 1920. Fighting corruption, even in government, was the key to his victory. “The real reason for his failure,” Crowe said of his opponent that year, “is that he is guilty and knows it.”

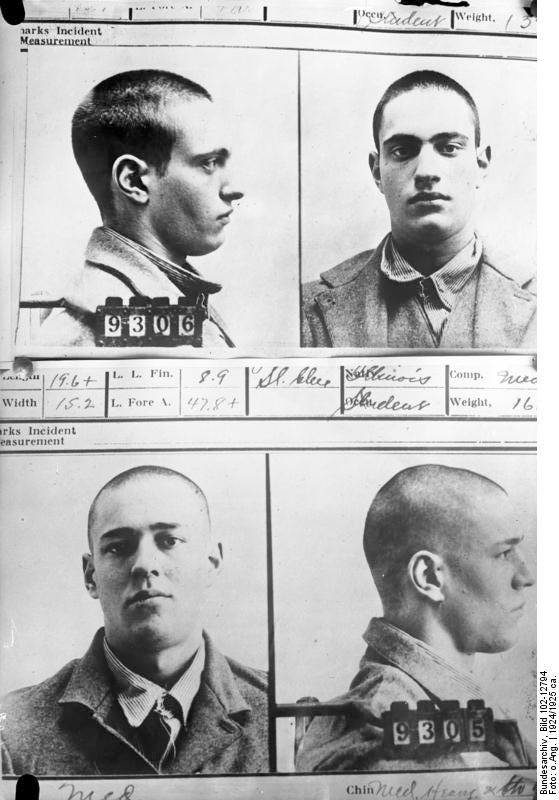

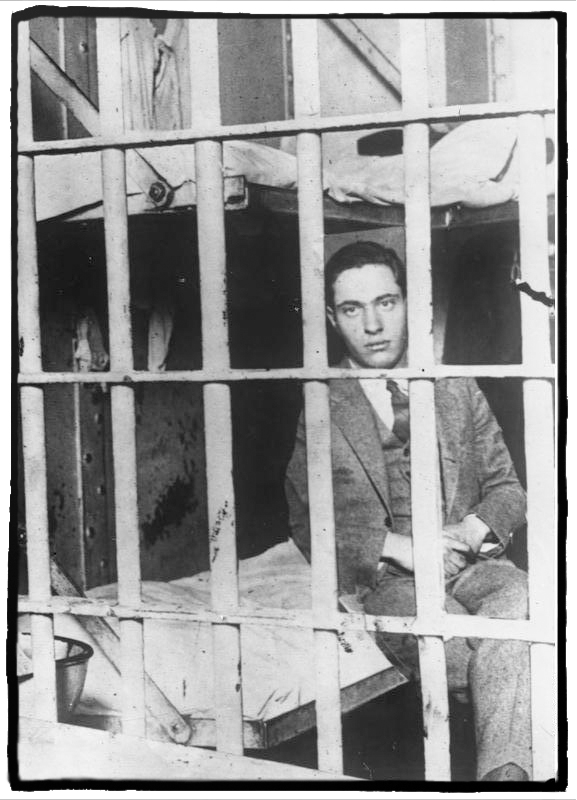

Crowe is best remembered as the prosecutor in the May 1924 murder trial of 14-year-old Bobby Franks. Two University of Chicago students named Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb—both 19 and from wealthy families—were arrested and charged with the crime. They confessed to abducting Franks, killing the boy and dumping the body in a forest preserve. Clarence Darrow, who had a reputation for defending the defenseless, was hired to take on the case. “It never occurred to me that I would refuse to defend anyone,” he once said.

By admitting they had killed Franks “for the thrill of it,” Leopold and Loeb were guilty… but of what punishment? The city was captivated by the senseless murder and subsequent trial. For a full month, they followed every word.

Crowe, who had a reputation for being tough on crime, pushed for the death penalty, but Darrow pushed back. He believed capital punishment did nothing to prevent crimes like these. Impulse, not fear, Darrow argued, guided violent tendencies. But a frustrated Crowe would have none of it. “The only useful thing that remains for them now is to go out of this life and to go out of it as quickly as possible,” he demanded.

Darrow would win the argument. Leopold and Loeb’s lives were spared, and both received life imprisonment sentences instead. Crowe was left to ponder whether the outcome was “a repudiation of his hang ‘em high brand of justice,” as one author put it.

Born in Peoria

Crowe’s biographical mention in books about Chicago history emphasizes his birth town, even if by short association. “[Peoria] was a city of distilleries and farm-machinery factories,” writes Dean Jobb in Empire of Deception, “considered so typically American that it became a truism of the entertainment industry that if an act was a hit in Peoria, it was a hit everywhere.”

Jobb points out that this was the town Robert Emmitt Crowe as a young boy was forced to leave. He made a name for himself elsewhere. But he was born in Peoria.

Ken Zurski is a longtime radio broadcaster, historian, storyteller and author. Follow his blog at unrememberedhistory.com. PM