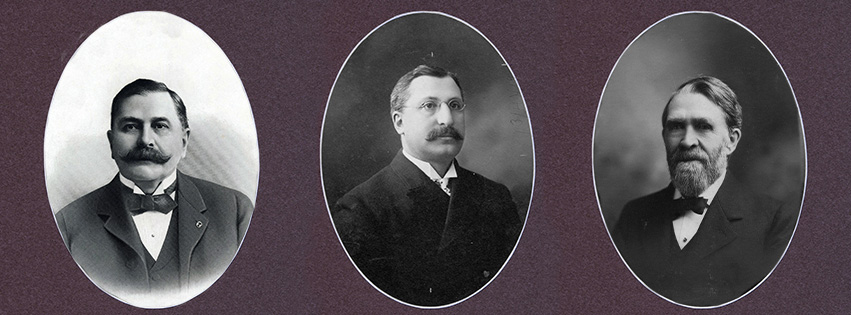

Legacy of the Whiskey Barons

The history of a community can connect people from all walks of life. No matter your race, gender, lifestyle or income, a physical location and its history—that “sense of place”—can be our shared heritage. Peoria, Illinois was once known as the Whiskey Capital of the World, producing more federal tax revenue from whiskey sales than anywhere else in the country—and the men who made it happen were called “whiskey barons.” Their efforts shaped the trajectory of our city, and their stamp of influence can still be seen today.

Distilling first came to Peoria circa 1844 when a local merchant named Almiran Cole transformed his flour mill into a whiskey distillery. By the following decade, the city’s population was booming as immigrants arrived from all over the world for plentiful job opportunities. With its central location and abundant natural resources, Peoria was the perfect site for a distilling hub. Its railroads were thriving, there were thousands of acres of fertile farmland, and the Illinois River provided steamboat transportation for people and goods alike. Dozens of others would follow Almiran Cole’s lead in the decades to come, with some 73 distilleries popping up in Peoria in the decades before Prohibition.

In addition to their business interests, Peoria’s whiskey barons were involved in a wide range of civic projects. They led the city’s cultural efforts, and their philanthropy shaped our buildings, churches, synagogues, clubs, schools, landmarks and libraries. Without the whiskey barons, Peoria would look much different today.

The Henebery Legacy

Matthew Henebery was born in County Kilkenny, Ireland in 1834, and his family left their homeland in the late 1840s during the great potato famine. Escaping death and impoverishment, the Heneberys headed to America—land of dreams and opportunities. By 1849, they had made Peoria their home.

Early in life, Henebery showed great promise as a businessman. He worked on the telegraph line that ran between Peoria and Chicago for a time, then went into the liquor industry in 1851, working with a man named Napoleon B. Brandamour, who soon made him a partner in a new Peoria distillery. Years later when their partnership dissolved, Henebery maintained the wholesale side of the business. Incredibly, his legacy lives on today via Henebery Spirits, which is now based in California.

A prominent leader in the Peoria community, Henebery served as a city alderman, vice president of First National Bank, and one of the first members of the school board. In 1857 he married Mary Daniels, who was also from County Kilkenny. The couple had a dozen children and were active in Peoria’s Irish Catholic community. They donated generously to the poor, to the hospitals and to Catholic Charities, and helped establish the local public library. The Heneberys even partnered with Bishop John Lancaster Spalding to develop the large tract of land in West Peoria which became Saint Mary’s Cemetery.

Matthew Henebery was also one of the organizers and builders of the Great Eastern Distillery, established in 1887. When he passed away in 1903, he left his wife in charge of a trust valued at over half a million dollars—about $15 million in today’s dollars. Mary Henebery continued their tradition of helping the poor by presenting Rev. John Quinn of St. John’s Parish with the Matthew Henebery Memorial School, which provided quality education in a poverty-stricken area of the city.

The Greenhut Influence

Born in Austria in 1843, Joseph B. Greenhut remains one of Peoria’s most intriguing historical figures. His father died when he was a young boy, his mother remarried, and the family moved across the ocean to Chicago in 1852. After training as a coppersmith, Greenhut enlisted in the Union Army and served in the Civil War, participating in the battles of Chattanooga, Gettysburg, Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville.

When the war was over, Greenhut returned to Chicago and rented a room in the home of Isaac Wolfner, whose son William owned a meatpacking plant. Greenhut built a strong friendship and business connection with William, which eventually landed the two men in Peoria in the 1870s. Wolfner served as director of the Commercial German National Bank and vice president of the National Cooperage & Woodenware Company, which produced all kinds of barrels, jugs and containers for beer and whiskey.

In 1886, Greenhut married Wolfner’s sister Clara. The couple had four children and were active in Peoria business, charity and society. An incredibly savvy businessman, Greenhut built a legacy of wealth and power that has proved long-lasting—including their beautiful mansion on High Street, which is still standing. Greenhut helped create the Distilling & Cattle Feeding Company, which he served as president, and was a leader at the Commercial German National Bank, Commercial Merchants National Bank & Trust, and the National Bank of the Republic of Chicago.

As much as the Greenhuts received from their community, they gave back to their community as well. They contributed to many national Jewish charities and donated locally to the Circle of Jewish Women and Peoria Hebrew Relief Association. Clara Greenhut served as one of the first vice presidents of the Peoria Women’s Club, the longest-running women’s club in the country, while Joseph donated much of the funds for world-renowned sculptor Fritz Triebel to create the Soldiers and Sailors Monument outside the Peoria County Courthouse. Greenhut was also the primary benefactor of the Grand Army of the Republic Hall, built for Union veterans of the Civil War in 1909. His enduring legacy in Peoria was summarized in History of Peoria City and County, published in 1912:

“It can be said of Mr. Greenhut, more than any other man, he has made Peoria commercially, for he has been connected with practically every business movement and enterprise of importance here.”

The Whiskey Trust

Joseph Greenhut was also famed for his role in creating the Distillers & Cattle Feeders Trust, better known as the “Whiskey Trust.” As president of the Distilling & Cattle Feeding Company, he mimicked the model created by John D. Rockefeller of the Standard Oil Company in 1882, consolidating dozens of small distilleries from various states into a single entity. This allowed the Whiskey Trust to control the sales, production and price of whiskey and limit their competitors’ ability to stay afloat, essentially forcing the smaller distilleries to join the trust—or go out of business.

After Congress passed the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, the Whiskey Trust began to face a host of legal and financial problems. Five years later, the Illinois Supreme Court declared the trust an illegal monopoly, and a significant rift developed which led to Greenhut’s departure. The Whiskey Trust ultimately restructured under a new name, American Spirits Manufacturing Company, though it never regained its market dominance. The company closed its doors in 1921.

The Greenhuts moved their family and business interests to New York, where they continued to donate to charities, both in New York and back in their former hometown of Peoria. Joseph Greenhut died in 1918, and he and wife Clara are buried at Salem Fields Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York. Today, while Peoria is no longer the Whiskey Capital of the World, the influence of the Greenhuts and other whiskey barons endures. PM