The Hidden History of E.S. Willcox

Close your eyes and imagine our city as a movie scrolling backwards in time. Every major event—from the Civil War to the groundbreaking of the Civic Center—and millions of personal stories, too, are captured and preserved within the walls of the Peoria Public Library. We are the keepers of these stories. But there is one story, unique to us, which isn’t well known but has impacted the entire nation. Have you ever heard of Erastus Swift Willcox?

Father of Public Libraries

The earliest recorded mention of a library in Peoria came in 1837, according to the Works Progress Administration’s “History of Peoria Libraries.” Although none was established at that time, the citizens of Peoria were interested in a place where they could share and consume information. Peoria had just been incorporated as a town two years earlier in 1835.

Twenty years later, Peoria had not one, but two libraries—established by a pair of clergymen with opposing theological views. According to E.S. Willcox:

“I doubt if the most cunning ingenuity could have contrived a more effective plan for starting a library in a small town, as Peoria then was, than by fanning just such a hot rivalry between opposing theological forces.”

![]()

Each congregation supported their own with books and funds. When the two libraries were consolidated in 1857 as the Peoria City Library, Willcox notes, “they had as choice a collection of some 1,500 volumes as probably any young library ever had in a city our size then.” But libraries of that era were not open to all. Members paid a subscription for access to information.

The reading room for the Peoria City Library was located at 73 Main Street, at the corner of Main and Adams, then moved to a room at 311 Main Street, about where the Apollo Theatre now stands. The German Library Association also formed in 1857 at the corner of Adams and Fulton, opening with 700 volumes.

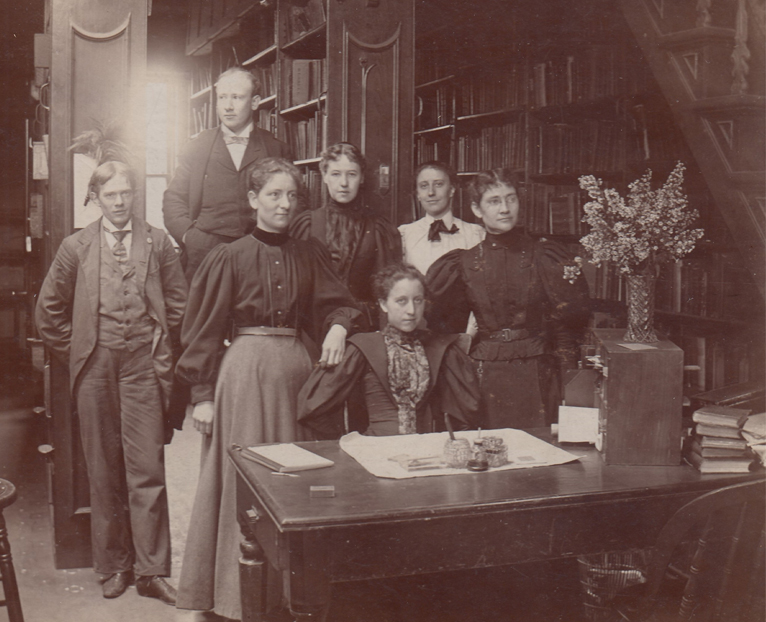

It was around this time that E.S. Willcox moved from Galesburg, where he taught modern languages at Knox College, to Peoria: “to avail himself of a business opportunity.” Having studied and traveled in Europe, Willcox was a scholar at heart and saw opportunities to bring culture and significant collections of books to Peoria. He was a leading force in establishing the Peoria Mercantile Library Association, which worked to raise funds for a larger library through lectures, plays, concerts and spelling bees.

But beyond raising funds for a larger building, securing valuable historic volumes for its shelves, and traveling to the East “to visit other libraries and acquaint himself with their best features,” Willcox’s lasting legacy to Peoria—and indeed, the entire country—was his idea to make libraries free for all.

Willcox believed that public tax dollars, not member subscriptions, should fund libraries. His friends discouraged him, but he persisted and drafted a law. As he explains:

“I placed it in the hands of my friend, Mr. Samuel Caldwell, in December 1870, who took it with him to Springfield, promising to do what he could to get it through the legislature, of which he was a member from Peoria. The bill was introduced by Mr. Caldwell [on] March 23, 1871, as House Bill No. 563, and as House Bill 563 it finally received the Governor’s signature and became law March 7, 1872.”

Illinois’ law established public libraries free to all municipal residents, permitted tax support, and outlined how they should be governed. This law was then adopted by 47 other states.

Building on a Rich History

As Peoria grew and became more prosperous, the library outgrew its rented rooms and buildings. In 1894, Willcox, in his annual report to city leaders, noted that 70 cities in the U.S. were larger than Peoria, but only 19 had larger libraries.

Ground was broken on July 11, 1895, for a building to be constructed of Lake Superior red sandstone, red brick and red stone trimmings. On January 25, 1897, Peoria Public Library moved from the Mercantile building to its new home in the 100 block of Monroe Street. Three lots were purchased at a cost of $16,000. None of the lots were on a corner, which was purposeful. Being on a corner lot meant your building would need two architecturally finished fronts, so interior lots were cheaper. By purchasing inside lots, they estimated savings of about $20,000.

According to Willcox’s speech at the grand opening, some 60,000 volumes were moved three blocks and put in order in six days by two men, seven high school boys and one team, at a cost of $221.91. The new Peoria Public Library opened on February 11, 1897, with great pomp and circumstance.

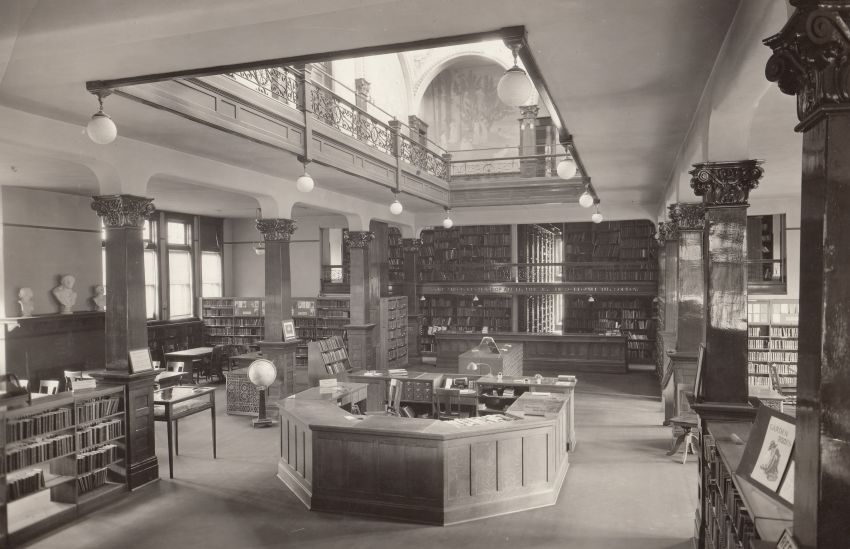

The new library building consisted of a front section of three floors and a back section of five floors. The front section held office space on the first floor, a reading room on the second floor, and classrooms on the third, while the back section held closed stacks for books. Built with growth in mind, only a fraction of the building was used at first. The library itself used only the second-floor reading room and closed stacks; the first floor was built to house offices for the school board so the library could earn some income.

The classrooms on the third floor were home to Peoria’s art and medical societies for years, while murals on the third floor and in the stairway were painted by artists F.C. Peyraud and H.G. Maratta. The largest mural, on the wall of the stairway, depicted a view of the Illinois River from Peoria Heights. Around the third-floor balcony were smaller murals related to education, poetry, music, literature, art, industry and science. Peyraud and Maratta painted them in 1896, and Peyraud stayed in Peoria for several years afterward to teach painting classes.

The original Peoria Public Library continued to meet the city’s needs for nearly 70 years. It was 30 years before the front section of the building was completely occupied by the library, and 40 years before the closed stacks in the back were fully utilized. But by 1964, the library needed more space. The beautiful old building could not meet the needs of the modern world, so the city once again embarked on a building project. The new Main Library opened in 1968—and it is still serving the city more than half a century later.

The beauty and benefits of libraries are timeless—and Erastus Swift Willcox knew that. In a key way, the farm boy from Knox County who made Peoria his home became the father of modern public libraries. His tombstone in Springdale Cemetery bears the inscription: “Father of Public Libraries. He rests from his labor; his works do follow him.” PM

Peoria Public Library is celebrating all libraries with the selection of The Library Book by Susan Orlean, our Peoria Reads! 2021 selection. Visit peoriapubliclibrary.org for related events and visit youtube.com/user/peoriapubliclibrary for a three-part series on Peoria Public Library’s history.