African Americans in U.S. Statecraft

Note: This article has been revised based on user comments.

The Peoria Area World Affairs Council is devoted to helping all of us, whatever our educational and cultural background, understand the fascinating and ever-changing world of foreign affairs and international diplomacy. In this history-themed edition of Peoria Magazine, we would like to introduce readers to the role African Americans have played in our country’s statecraft across the centuries. We are also pleased to introduce readers to a homegrown global diplomat here in central Illinois.

America continues to play an outsized role on the world stage. While a large part of American influence is a function of economic power, diplomacy is the tool that enables nations to use that economic power, along with soft power and other assets, to achieve specific goals.

Black Americans in Diplomacy

Black Americans were involved in diplomacy earlier than in many other areas of government. “The U.S. Department of State was the first major government department to appoint Blacks to positions of prestige, during the period from the Civil War to the 1920s, when more than sixty African Americans were appointed to diplomatic, consular or commercial agency positions,” as Allison Blakely wrote in African Americans in U.S. Foreign Policy.

The country’s first official diplomat was appointed in 1869, only four years after the close of the Civil War. Ebenezer D. Bassett was named U.S. minister resident to Haiti and “oversaw bilateral relations through bloody civil warfare and coups d’état on the island of Hispaniola. Bassett served with distinction, courage and integrity in one of the most crucial but difficult postings of his time,” according to Christopher Teal on BlackPast.org. Even Bassett’s 1869 appointment was preceded in 1845 by William A. Leidesdorff’s role as U.S. vice consul in California, which then belonged to Mexico.

The first official ambassadorial appointment was a milestone that came much later. But in between, diplomatic service was more open to Black Americans than many other professional career tracks. For example, Mifflin Wistar Gibbs, the first African American municipal judge in U.S. history, was appointed U.S. consul in Madagascar in 1897. The first Black ambassadorial appointment became official in March 1949 when Edward R. Dudley made history as ambassador to Liberia. He was followed four years later by the second Black ambassador, Jesse D. Locker.

There were, however, roadblocks. It was not until later that Black Americans served as ambassadors to nations with non-Black populations. This de facto limitation left African Americans shut out of some of the crucial postings of the Cold War era.

Other milestones from early in that period include the first African American Nobel Peace Prize laureate in 1950, Ralph J. Bunche, and the first Black U.S. delegate to the United Nations. Some consider this to be Edith S. Sampson, Illinois’s first Black elected judge, in 1950, although technically she was an alternate delegate. In that case, the distinction would go to Andrew Young in 1977.

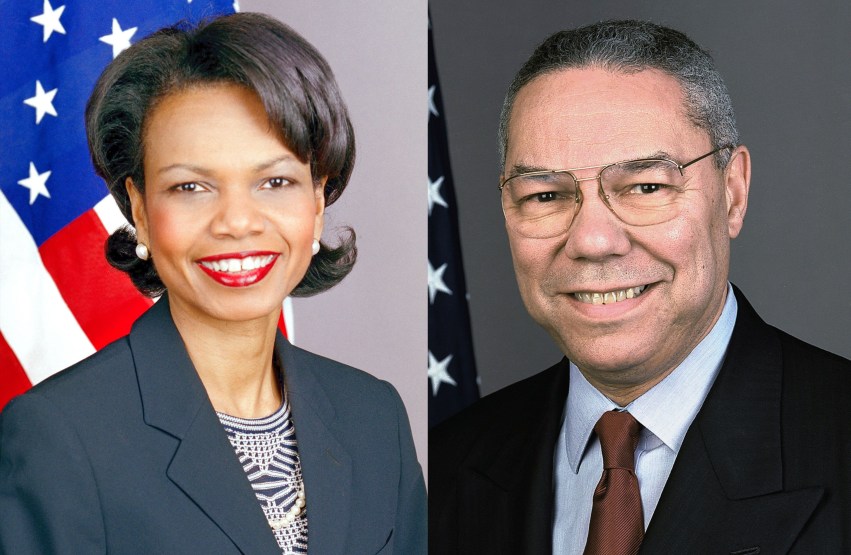

Since that time, the United Nations has seen many Black Americans serve in high ranks. Ten Black Americans have served as U.S. ambassadors to the U.N. or the equivalent—most recently Susan Rice during the Obama administration and Linda Thomas-Greenfield in the Biden administration. In addition Colin Powell made history as the first African-American Secretary of State, while Condoleeza Rice was the first African American woman in that position.

United Nations Bodies

The United Nations has many constituent bodies, each with a specific purpose. UNESCO manages world heritage sites, along with cultural and education matters. Many people will be familiar with UNICEF, which deals with improving the lives of children around the world, or the World Food Program, which works to end global hunger.

Another body within the United Nations is the UNHCR: the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. For 70 years, this organization has been “protecting people forced to flee” from war, famine, atrocities, natural disaster, genocide and the other untenable conditions.

International work in support of refugees calls for a special kind of service. Working on behalf of refugees takes not just compassion and endurance, but also a humble heart and a servant mentality. It requires all the skill of the diplomat in facilitating cooperation among governments, all the empathy of grassroots philanthropic work, and all the organizational and leadership capacity of highly seasoned executives. Enter Will Ball of Peoria.

Peorian on the World Stage

Will Ball’s career is in some ways a fairly typical Peoria story: a successful multi-decade career as an executive with Caterpillar Inc. including service across multiple departments, an overseas assignment, a series of promotions, and finally his retirement after 33 years of service. His story also takes an unusual turn, thanks to his desire to fill his life with “challenging, rewarding and fulfilling experiences in service to others.”

For the last several years, Mr. Ball has served as a volunteer involved in global issues, and he has done it primarily from Peoria. While not everyone will be asked to serve on high-level boards, his story suggests that it is possible for real people to engage meaningfully with significant global issues from right here in central Illinois.

Since 2015, Ball has been on the board of the USA for UNHCR, an independent nonprofit body that supports the work of the UNHCR. He now serves as secretary of the board. Envisioning a world without refugees—where all refugees can transition to permanent and sustainable lives—USA for UNHCR “protects refugees and empowers them with hope and opportunity,” in addition to providing for education, training and basic needs such as food, water, shelter, medical care and safety.

Although a career Caterpillar exec and not a diplomat by training, Will Ball ended up on his mission to bring aid to refugees through his professional experiences. One major assignment of Ball’s career was heading the Caterpillar Foundation, the company’s philanthropic arm. During his tenure, Ball expanded the foundation’s global footprint from 20 to 70 countries worldwide. Having directed this massive scaling-up, Ball had abundant experience in philanthropy to prepare him for his role at USA for UNHCR.

Less obvious, though, is how another part of his career prepared him for the work: serving as a registered corporate lobbyist in Washington, DC allowed Ball to develop his advocacy skills. It’s obvious when talking to him that he is a tireless and effective advocate for the cause of refugees worldwide. “What’s misunderstood is that no one chooses to be a refugee,” Ball explains, “to rush themselves out of their homes, businesses, communities—usually at a moment’s notice—to keep their families safe.”

He also points to a New American Economy report which demonstrates that refugees are entrepreneurs to a larger extent even than other immigrants—both of whom outstrip American-born workers in this metric. “We can learn a lot from their resilience and spirit,” Ball notes.

Reducing the Refugee Crisis

Whether through advocacy or fundraising, diplomacy plays a key role in Ball’s work. “Finding diplomatic solutions to the conflicts fueling the refugee crisis is imperative to reducing the world’s refugee crisis—greater now than at any time since the end of World War II,” he explains. A full one percent of the world’s population are refugees, and the period in which displaced people have to live in camps is longer today than ever—17 years on average. According to Ball, attacking the problem requires a coordinated international response to address the factors triggering displacement, and this work needs to be done at “the big table,” the UN Secretariat and the Security Council, as well as the UNHCR.

At the individual level, Ball notes that even the smallest of financial contributions can make a significant difference in the lives of refugees. “But the more meaningful way to get involved,” he adds, “is to spend some time getting educated on the refugee crisis because more often than not, there are ways to get involved in your local community.” For example:

- Business owners can find skilled workers among resettled refugees in the area.

- Tax-paying citizens can advocate to local, state and national leaders in support of equal access to COVID-19 vaccinations for refugees and for increasing the numbers of resettled refugees America takes in each year.

- Follow USA for UNHCR and UNHCR on social media. Subscribe to their newsletters. Spread the word.

Encouraging Ball every step of the way is his wife Mimi, daughter of an Ethiopian UN diplomat who grew up around the world—wherever her father’s work with the World Food Program took the family. Ball credits her for helping him to develop an understanding of geopolitics and global issues. The couple has three daughters. Ball also serves as chairman of the Board of Trustees of Eureka College and as second vice chair of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library Foundation. PM

To learn more about the Peoria Area World Affairs Council, visit pawac.org.