A Snapshot of the American Mosaic

“Lamentable is the fact that during the six days given over to Creation, picnic tables and fireplaces, foot bridges, toilet facilities, and many other of man’s requirements even in natural surroundings, were negligently and entirely overlooked. This grave omission, his persistent efforts have long endeavored to supply, with varying success, or lack of it, as one may choose to view it.

Confronted with this no less than awesome task of assuming to supply these odds and ends undone when the whistle blew on Creation, man may well conclude, pending achievement of greater skill and finesse, that only the most persistent demands for a facility shall trap him into playing the jester in Nature’s unspoiled places. He may well realize that structures, however well designed, almost never truly add to the beauty, but only to the use, of a park of true natural distinction. Since the primary purpose of setting aside these areas is to conserve them as nearly as possible in their natural state, every structure, however necessary, can only be regarded as an intruder. Confronted with the so-called development of such areas for his own greater use and enjoyment, he has on occasion recognized these first principles, to the masterly accomplishment of rejecting, sometimes with a semblance of consistence, the temptation to embellish Nature’s canvas. He has sometimes even confined himself to building only such structures as long and thoughtful consideration demonstrates he cannot do without. The success of his achievement is measurable by the yardstick of his self-restraint.”

—Excerpt from “Apologia” at the beginning of Park Structures and Facilities, published by the U.S. Department of the Interior; National Park Service; Albert H. Good, architect, State Park Division, chairman and editor; 1935 (updated 1938)

With architect Albert Good’s delightfully expressive design philosophy as a backdrop, the African-

American Company No. 1743 of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Civilian Conservation Corps created the Thunderbird Lodge at Missouri’s Washington State Park just outside Metropolitan St. Louis. Purpose-built in the early 1930s as a dining lodge, it has served in contemporary times as a welcome center and store for park visitors and campers.

In 2019, this historic jewel was lovingly rehabilitated to its original glory. The Lodge, as part of an ensemble of structures that comprise the Washington State Park CCC Historic District, offers all who experience it a stunning synergy of American history, cultural diversity and quiet architectural beauty.

Washington State Park

Washington State Park, located in the eastern Ozarks off Highway 21, was established nearly 90 years ago. What makes this park so unique from many others are its shared Native American and African American histories. The park contains the largest group of petroglyphs, or Native American rock carvings, discovered to date in the state of Missouri. These carvings were first created by the Mississippian branch of Native Americans around AD 1000, and while some of them are very weathered, their number and overall quality at the park are quite spectacular.

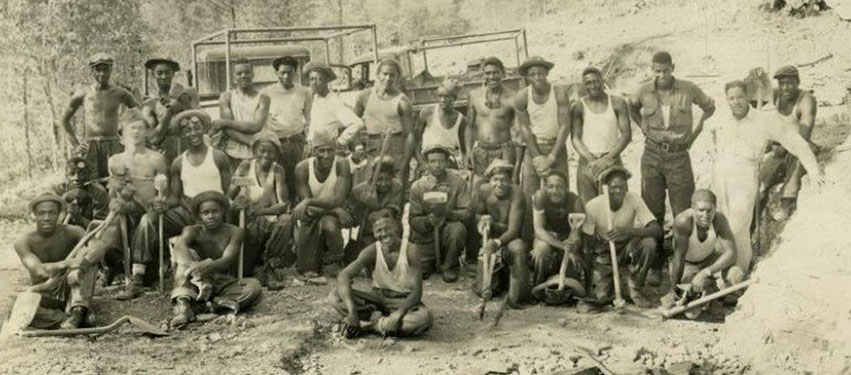

Not long after the park land was donated to the state, an African American company (No. 1743) of the federal Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) began to develop the area, continuing their work from 1934 to 1939. This CCC company lived in the park while undertaking their projects. Inspired by the Native American petroglyphs, the company christened their barracks as Camp Thunderbird. When they built their dining lodge, they carved the Native American thunderbird symbol into the building’s stone chimney, as well as including it in their handmade iron door hinges and other building embellishments.

The Company’s stone masons also did extensive roadside work, laid stone for what is known as the 1,000 Steps Trail, and worked on 14 other buildings, including an equally handsome octagonal lookout shelter. Most of the stone for these structures was quarried in the park, and some of the timbers were cut there, too.

Two of the three Native American petroglyph sites in the park, as well as many of the CCC company’s buildings, have been included in the Washington State Park CCC Historic District, listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1985.

Thunderbird Lodge

Built directly over a tributary of Missouri’s Big River, Thunderbird Lodge is a terrific example of the gentle and rustic architecture espoused by its architect. The rough-hewn stones, the wood structural elements and trims, and the blacksmith-forged iron works all contribute to a very quiet, profound beauty. The fact that the entire structure is essentially a bridge as well only adds to the lodge’s unique architectural lineage.

At the same time, that Big River location made Thunderbird Lodge susceptible to flooding, which caused the State of Missouri to close the aging building in 2017. Ultimately, given the lodge’s perfect confluence of American history, cultural diversity and architectural clarity, the State made the decision to comprehensively rehabilitate the lodge, address the flooding issue, and provide historically accurate updates to other surrounding features within the park. The rehabilitation of the building itself included such features as a new wood shake roof, historically appropriate windows and doors, new flooring and wall coverings, and accessibility upgrades.

Snapshot of the American Mosaic

The Thunderbird Lodge brings to the “table of history” four incredibly significant elements that combine to provide a wonderful snapshot of the diversity of the American mosaic. First of all, it is located amidst the former home of an important Native American culture, a culture that is visibly expressed in many details of the lodge. Secondly, it was born of the Great Depression, one of the most pivotal and transformational events of the 20th century. Thirdly, not only was it born of the Great Depression, but it sprang from a unique facet of the country’s response to that calamity: an African-American company of the President’s Civilian Conservation Corps. And, last but by no means least, it is a consummate example of the humble and unassuming “rustic park architecture” very much championed during this same era.

For these four reasons, the Thunderbird Lodge is a powerful reminder and celebration of the profound significance and value of the American mosaic. Its recent renewal would most likely have received a positive nod from architect Good, given this further message from his Park Structures and Facilities credo:

“Successfully handled, rustic architecture is a style which, through the use of native materials in proper scale, and through the avoidance of rigid, straight lines and over-sophistication, gives the feeling of having been executed by pioneer craftsmen with limited hand tools. It thus achieves sympathy with natural surroundings and with the past.” PM