A Meeting of Giants

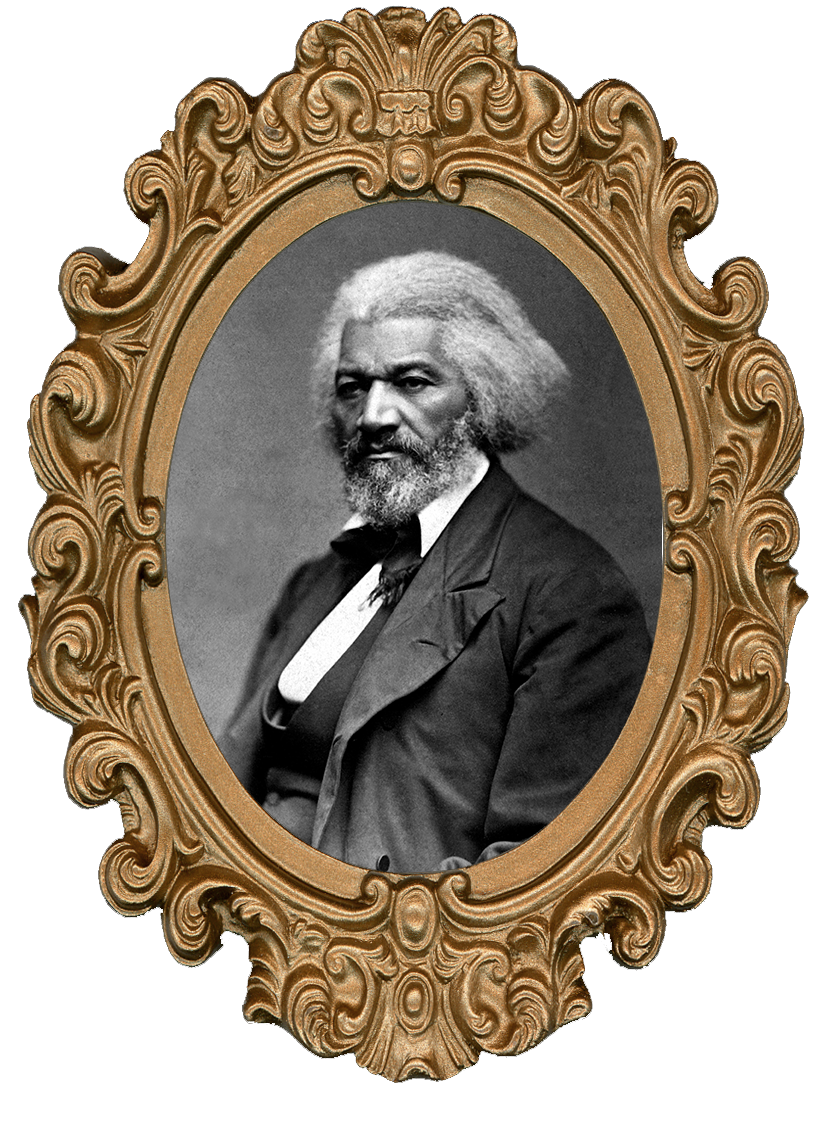

Two of the greatest personalities of the 19th century met for the first time on a cold February morning in Peoria. The year was 1870 when Frederick Douglass, the great reformer, writer and orator, dropped by the home of Robert Ingersoll, “free thought” evangelist and the city’s most illustrious citizen, who was then serving as Illinois attorney general.

Visit From a Stranger

Crossing the country on a speaking tour, Douglass had addressed a crowd in nearby Elmwood the previous evening. He was told that if he needed accommodations in Peoria—a city where he had been unable to secure a hotel reservation on a previous visit—he should call on Ingersoll. “It would not do to disturb a family at such a time as I shall arrive there on a night as cold as this,” Douglass protested in his autobiography. But he was assured Ingersoll would receive him warmly, regardless of circumstance.

Now a recognized celebrity, Douglass reported finding quarters that night “at the best hotel in the city.” His curiosity aroused, however, he decided “to know more of this now famous and noted ‘infidel’”—the man who reportedly would have taken him in. Before leaving to catch his train, Douglass paid a morning visit to the Ingersoll home. His published account reads:

“Mr. Ingersoll was at home, and if I have ever met a man with real living human sunshine in his face, and honest, manly kindness in his voice, I met one who possessed these qualities that morning. I received a welcome from Mr. Ingersoll and his family which would have been a cordial to the bruised heart of any proscribed and storm-beaten stranger, and one which I can never forget or fail to appreciate.”

The experience also moved Douglass to speculate openly about matters of faith in an Ingersollian vein. “Genuine goodness is the same, whether found inside or outside the church, and that to be an ‘infidel’ no more proves a man to be selfish, mean and wicked than to be evangelical proves him to be honest, just and human,” Douglass wrote. “Perhaps there were Christian ministers and Christian families in Peoria at that time by whom I might have been received in the same gracious manner… but in my former visits to this place I had failed to meet them.”

Kindred Spirits

Ingersoll and Douglass were kindred spirits in many respects. Not only were they among the most gifted—and busiest—speakers of their day, both were heavily involved in politics, urging equal rights for African Americans and women when those causes were anything but popular. In 1883, 13 years after their first meeting in Peoria, Douglass and Ingersoll both raised their voices to oppose the Supreme Court’s ruling that invalidated the Civil Rights Act of 1875, which had been enacted in response to civil rights violations against African Americans.

“The difference between colored and white here is that the one, by reason of color, needs legal protection, and the other, by reason of color, does not need protection,” Douglass said. “It is nevertheless true that manhood is insulted, in both cases. No man can put a chain about the ankle of his fellow man, without at last finding the other end of it fastened about his own neck.”

“The decision takes from seven million people the shield of the Constitution,” Ingersoll said about the decision, which allowed states to set their own restrictions for minority citizens. Ingersoll’s speech on the occasion spanned 50 pages.

Both Ingersoll and Douglass became national figures for supporting causes that were considered controversial. Douglass, a former slave, focused on abolishing slavery while advancing the rights of women and African Americans. Ingersoll took on organized religion while still promoting so-called Christian ideals, notes Susan Jacoby, author of The Great Agnostic, a 2013 biography. He also campaigned passionately for women’s rights, against racism, and in opposition to the death penalty.

Promoters of Freedom

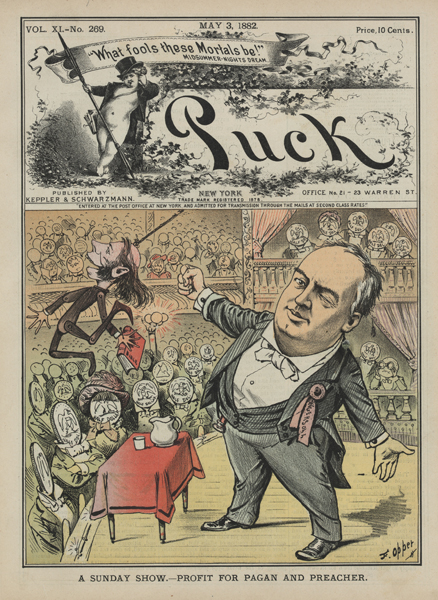

At a time when attending speeches and lectures was a popular form of entertainment, Ingersoll is said to have delivered more than 1,300 in his career. “More people probably heard his voice than any other American prior to mass media,” notes Tom Krupa, who became interested in Ingersoll while volunteering at the Peoria Historical Society’s Flanagan House at 942 NE Glen Oak Ave. The house, built in 1837, displays a portrait of Ingersoll and a desk he used while living in Peoria from 1857 to 1877. A successful attorney, Ingersoll later moved to Washington, DC and New York City.

Douglass was also a traveling man, visiting Peoria on at least three occasions. His message—before, during and after the Civil War—called for equality for all Americans. One of his most famous speeches took place in 1852 at a Fourth of July celebration in Rochester, New York, where he told the predominantly white audience: “What to the slave is the Fourth of July? This is the birthday of your national independence. You may rejoice, I must mourn.” Douglass never stopped promoting freedom. It should be remembered that on the last day of his life, in 1895, he attended a meeting of the National Women’s Council in Washington, DC.

Ingersoll likewise supported women’s rights while covering a wide variety of subjects, most notably criticizing organized religion. “With soap, baptism is a good thing,” he once famously quipped. “That Ingersoll made a good living out of questioning religion particularly enraged his opponents,” wrote Jacoby. What set him apart from the crowd was his erudition and good humor. “He called Shakespeare his Bible and Burns his hymnal,” Krupa notes.

Among Ingersoll’s many admirers was no less than Mark Twain, who also became successful on the lecture circuit. “It was just the supremest combination of English words that was put together since the world began,” Twain wrote to his wife after witnessing an Ingersoll speech. “Lord, what an organ is human speech when it is played by a master.”

Powerful Influences

The Douglass visit with Ingersoll that took place 150 years ago represents a special moment in American history when two giants of the “freethinking” world came together.

During the Civil War, Douglass made a speech that pointed to the power of photography, a technology that by then had spread across the country. Even small towns had photo studios, he said. “The universality of pictures must exert a powerful though silent influence upon the ideas and sentiment of present and future generations,” Douglass stated. I only wish we had a picture of these two giants when they met in 1870 in Peoria. PM